21 Jan Nasty Women of History and Art

It seems unbelievably dated, but people are still calling ambitious, intelligent women “nasty women.” As if that could hurt anyone’s feelings in 2020! In fact, like many other outdated insults, it has the opposite effect. Many women today are are taking the term on (as lesbians took on the term ‘dyke’) and calling themselves “nasty women” in sarcastic protest.

In this spirit, I would like to offer up a few women who were “nasty women” in the past, but nasty only in this sense. They were ambitious and intelligent, even fairly aggressive—women certain men would call “nasty.” And also, at least in many cases, they struggled with misogyny. Some of them had to overcome social limits on women’s activities; some were hated for their successes; some were even remembered in inaccurate, misogynistic ways.

Ancient Queens

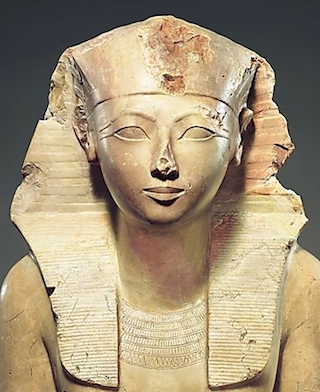

To show that there have *always* been ambitious, “nasty women,” let’s start in the distant past, with a female Pharaoh, Hatshepsut, who ruled over Egypt from 1478 to 1458 BC. Hatshepsut came to power when her husband died, leaving only one male heir, a 2 year old baby. So Hatshepsut was appointed as regent, to rule in the boy’s place. But Hatshepsut did not just rule until the boy was an adult, she ruled for the rest of her life. And she was an important Pharaoh. She established some of Egypt’s most important trading relations and built herself one of the most significant funerary temples.

It is, however, noticeable that all of the statues of her are broken or cracked. Even this famously beautiful one that portrays her frankly as a woman (while in many she appears as Pharaoh, and hence a man) is damaged. This is because all of her statues were smashed after her death. We are not quite sure when this happened, or why. Given, however, that she was also left out of the ancient Egyptians’ king lists, it seems likely that it happened at least in part because she was a woman.

First Professional Women

Before the 17th century, most of the ambitious “nasty women” we know about were rulers or mistresses of powerful men. Starting in the 17th century, however, there was a new category of woman: the professional. Many of the professions that women occupy today, such as doctor or lawyer, were still closed to women, but for the first time there were professional women actresses, such as Nell Gwyn (also the mistress of Charles II of England), writers such as Madame de la Fayette or Aphra Behn, and painters—such as Artemisia Gentileschi. Like many early women painters, Gentileschi was the daughter of a prominent painter, Orazio Gentileschi. His daughter was the child who inherited his talent, and he had her trained in his profession. Unfortunately, however, the painter he hired to tutor her raped her, or at least pushed her into sex, among other things with promises of marriage. But when it turned out that he was already married, the Gentileschis took him to court—an amazingly bold move for their time—and won!

Artemisia went on to have an impressive career as an artist. Her most famous painting, however dates from just after the trial. Like many of her paintings, it depicts one of the heroines of the Bible, and like a number of her heroines, this one is a self-portrait. The painting depicts the heroine Judith cutting off the head of the general Holofernes after they have had sex. It is hard not to see an autobiographical charge here: this isn’t what we usually call “revenge porn,” but it is probably a kind of revenge porn nonetheless.

The Suffragette Era

I want to conclude with one of my favorite John Singer Sargent portraits. *Not* “Madame X:” that is a wonderful portrait, but Virginie Gautreau’s only ambition was to be beautiful, and to my mind, that doesn’t count as a real ambition—though she certainly did have an interesting way of presenting herself. Instead, I am going to talk about the woman whose portrait hangs next to “Madame X” at the Metropolitan Museum: Edith Minturn Stokes. Although the portrait dates from 20 years before women got the vote, Stokes was already politically active: she created a sewing school for immigrant women and was the President of the New York Kindergarten League, fighting for universal kindergarten. And she looks the part: with her husband dimly lit in the background, she looks straight out of the painting, as if she were about to step down and shake your hand. Also, in contrast to every other woman in the Metropolitan’s collection, she is dressed for action: with her practical skirt (several inches off the ground for walking) blouse, jacket and tie—and her hair tied back to look like a boy’s—she can move freely, and from her high color, you can see that she has in fact been outside walking. It is a remarkably modern image, and she was a remarkably modern woman.

Want to learn more about the ambitious “nasty women” of history and art? Take our Nasty Women tour of the Metropolitan Museum some weekend!